| ZNet Commentary

September 06, 2003 Trade Talk: Speaking in Tongues

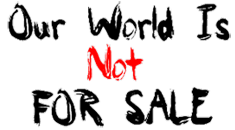

By Aziz Choudry It's enough to make your eyes glaze over. Modalities. Conditionalities. Most-favoured nation. Rules of Origin. Phytosanitary Standards. TRIPS. TRIMS. GATS. WTO. APEC. FTAA. NAFTA. Trade negotiators, governments, the media and many non-governmental organisation (NGOs) are pumping out material brimming with an alphabet soup of acronyms and jarring technical jargon. The torrent seems particularly bad right now. Another World Trade Organisation (WTO) Ministerial meeting looms imminently, with a November Summit of the Americas not far behind, where trade ministers and officials will meet to discuss the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), a trade and investment agreement between all of the countries in the Americas except Cuba. The arcane language of trade negotiations and global economics resembles the incomprehensible utterances of those who, in a state of apparent religious ecstasy, believe themselves moved by a divine force - and speak in tongues. Whether it is a belief in salvation by God or the global free market economy, "true believers" frequently feel that they alone have the truth, the light and the way. The inaccessibility of this language remains a big plus for the economic interests - governments and corporations - behind initiatives like the WTO and FTAA as they seek to mould the world so that global capital can do what it likes, when it likes, how it likes, and with whomever it likes. It is as though they have devised a secret code to keep most of us none the wiser about what they are doing and not particularly interested in finding out, either. That is a surefire way to minimise popular understanding, public

debate and dissent. The dense, confusing jargon and the rather abstract-sounding nature of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT - which established the WTO) led to the subject being dubbed a "ratings killer" by New Zealand media some years ago. It has only been popular

education and action on these and other agreements - especially mass mobilisations and non-violent direct action - that have focussed any public attention on them. Deconstructing and demystifying the WTO and global economics through popular education in terms that we can all understand is an important task if we are to reach out beyond activist and NGO networks and build genuine mass movements that can seriously contest the power of global capital and local elites. But those of us who closely follow trade negotiations with morbid fascination and concern like soap opera addicts also have a tendency to adopt this gibberish. Perhaps there is something hypnotic and strangely seductive about these words , once we have figured out what they mean. After the initial bewilderment and alienation, they seem to become rapidly

incorporated into our own vocabulary. Then we want to proudly show off our new words. Why do so many NGOs critical of the WTO spend so much time speaking the same language as the trade bureaucrats? Is it to seek legitimacy in the eyes of officials and institutions? "Take us seriously, we can use long and complicated words and phrases too." Is it an initiation rite into a cozier world away from the fraught and unglamorous work of mobilizing in communities? "I'm not one of those nasty anti-capitalists - let's talk about modalities." When we try to fight them in their language we risk sacrificing the power to name our world and assert our values. Policy analysis, research and advocacy are important but these must be directed by and used to advance the needs and demands of grassroots struggles, not the interests of NGOs which want to maintain good relations with governments and officials by showing that they speak and understand the same language - literally and figuratively. Unsurprisingly, that language tends to exclude criticisms of colonialism, capitalism or imperialism. The framing of issues in this language, and the narrow focus on technical aspects of texts and official processes is hardly conducive to popular education for mobilization, and indeed shuts out the majority of our societies. This addiction to technical jargon tends to obscure, rather than advance popular understandings of these processes and institutions and their effects on our lives. It inevitably permeates our "popular education" resources. It runs the risk of connecting only with a very small segment of societies in certain NGOs and activists who eagerly read the regular email bulletins on WTO negotiations. Without being connected to broader political, economic and ecological questions, and struggles for justice and dignity on the ground, their activities and analyses can seem as disconnected from on-the-ground reality as the heady world of trade bureaucrats. Writing about "NGOism", US global justice activist Patrick Reinsborough says that there is a "terrifyingly widespread conceit among professional "campaigners" that social change is a highly specialized profession best left

to experienced strategists, negotiators and policy wonks. NGOism is the conceit that paid staff will be enough to save the world." I have nothing against sound critical policy analysis but I worry about the way in which this language in the gospel according to the WTO (or the FTAA, World Bank, IMF, etc) comes to frame so much of what we do and say. It is

all-too-easy to develop a severe case of tunnel vision from poring over complex wordy documents and to adopt the bizarre compartmentalization of life-and-death issues which the agreements, provisions, articles and clauses of official texts lend themselves to. Some NGO policy analysts do excellent work in monitoring negotiations and disseminating information. They are able to expose concrete examples of the anti-democratic processes and powerplay that characterizes WTO negotiations. But there is often a real sense of disconnect between their priorities and the priorities and struggles of peoples' movements. Many people most directly affected by neoliberal policies and mobilising at the grassroots may not be familiar with the jargon but have a keen understanding of what is going on and a bigger picture analysis which is often missing in the world of professionalized NGO policy analysts. The devil lies not only in the details of trade and economic agreements, but in the underlying economic, social, political and environmental agendas underpinning them. Too many of the analyses of trade negotiations have too little political analysis. We fetishise the minutiae of these agreements at the risk of losing sight of the fact that they are manifestations of bigger systemic problems - like capitalism and colonialism. A certain elitism has already developed in global justice networks where policy "experts" in relatively well-resourced organisations are elevated to guru-like status and get to interpret the texts and meanings of meetings for the rest of us. These interpretations - and the accompanying suggestions for action are often divorced from the lived realities of daily struggles for justice and dignity, and a political analysis of the bigger picture. They often urge reformist solutions to try to change or insert some words here or there, rather than challenging the underlying values and principles on which the agreements are based, or heeding popular demands for radical transformation of the prevailing economic order. We need to be wary of the development of an emergent class of high priests of policy analysis, who are claiming the space, authority and mandate to set strategy and direction of global justice movements. The gulf between them and the aspirations of peoples' struggles needs to be acknowledged and addressed. If anyone is going to save the world from the

ravages of neoliberalism, it will be community mobilizations and mass movements, not professional NGOers speaking in tongues. |